As I’ve mentioned before, I love discovering interesting old books.

Recently, I discovered The Century Reader: Humorous, Serious and Dramatic Selections, which has me musing on whether we might be better off by avoiding the latest in high tech and working on some more old-fashioned skills instead. This leads me ponder two books and a two movies.

The books are Three Men in a Boat, Jerome K. Jerome’s comic account of a boat trip up the Thames in late-Victorian England, and Frank Herbert’s Dune, the epic novel of ideas, spanning ecology, the nature of power, the potential of the human body and mind, and much more.

The movies are Dune, Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 adaptation of part of Herbert’s book, and 1999’s The Matrix from the Wachowski sisters, another exploration of ideas, virtual worlds and embodiment. I’ll leave the various sequels aside, as the ideas that interest me are in the two first films.

Does anybody still read Three Men in a Boat? Fans will recall the uncanny ability of J.’s friend Harris to spoil a party by by announcing that he’ll sing a comic song, only to ruin the mood by failing to remember the words – and even the tune – in a most embarrassing fashion.

Away from the comedy, though, this was an important part of people’s lives in the centuries before mass media turned us all into cultural consumers. Ordinary men and women entertained each other by reciting poetry, and performing songs or soliloquies.

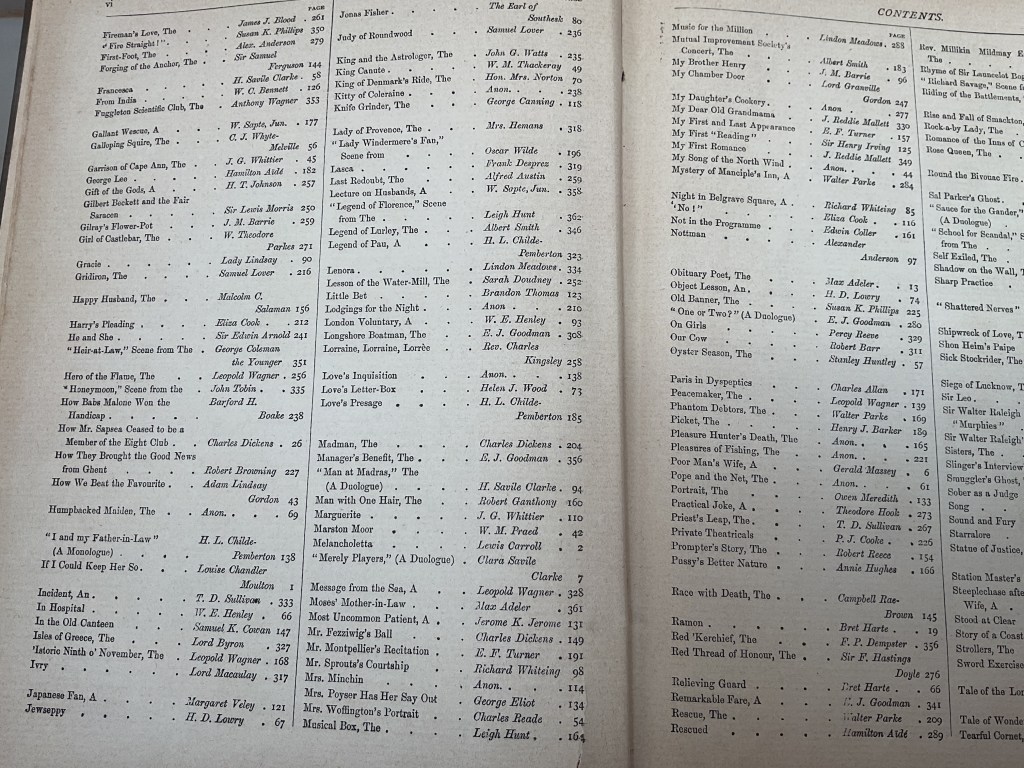

The Century Reader was compiled by H. Savile Clarke and Leopold Wagner and published in 1895, just a few years after Three Men in a Boat. It contains 332 texts to be memorised and recited: poems, dramatic narratives, and dialogues – many of which stretch over multiple pages.

Learning even a small number of these by heart would require a capacity for memorisation which I certainly don’t possess. Indeed, I don’t know anyone who does, outside of a few actors, professional or amateur. After all, we’ve long ago outsourced “remembering things” to our electronic devices, haven’t we?

Since the purpose was to recite these pieces for an audience, many other acting skills were needed as well, so the book’s introduction includes guidance on the effective use of voice and gesture – the skills needed to captivate the audience and transport them from the here and now into the world of the story.

This is where I begin to think about Dune.

In both novel and film, the young Paul Atreides is surrounded by individuals who have mastered aspects of human potential.

Duncan Idaho and Gurney Halleck are masters of martial arts: they are supreme warriors. Idaho is also a diplomat; Halleck, a minstrel. Thufir Hawat exemplifies the abstract mind; he has a vast talent for memorisation and logical analysis. As a Master of Assassins he has skills ranging from psychological analysis, to military strategy, to the physiological and chemical principles of poisons. Paul’s mother, the Lady Jessica, has been trained by the Bene Gesserit sisterhood in the use of voice as a tool for controlling other people: an art which requires a deep understanding of the link between vocalised language and the psyche, encompassing cultural contexts, social status, and the role language plays in mediating our experience of reality. She’s been deeply trained in embodiment: she has full control over even the smallest muscle in her body, and the ability to sense and direct her own physiological processes.

Paul has been trained from birth to acquire the skills of each one of his teachers. He represents, in fact, someone who manifests the full development of human potential.

Of course, Dune is a novel and Herbert can provide his characters with powers far beyond those possible in the real world – but the truth is that most of his characters’ abilities are simply exaggerated versions of things that we could actually learn to do, given time, motivation and training.

Herbert’s focus on maximising human talent has an in-universe justification. It’s a response to an ancient threat: sentient machines, or AI. I haven’t read any of the prequel novels by Herbert’s son which describe this; it’s enough to know that computer intelligence once subjugated humans, and were purged after a rebellion. in the aftermath, humans determined to replicate what computers had once done with their own minds.

And that’s what leads me to The Matrix: a world in which humanity exists in a virtual reality controlled by sentient computers. It’s a world which seems to be creeping nearer and nearer each month.

Apple is following Google in trying to introduce wearable goggles which mean we can walk around in utterly realistic virtual worlds, or in the real world overlayered with digital constructs (augmented reality). Elon Musk is investing huge resources into making us cyborgs, with chips implanted in our brains: before long, we may not even need the goggles.

AI bots are now embedded in more and more of the tools we use, harvesting data about our behaviours and preferences to the point where they can predict what we want before we know it ourselves. Other AI tools impersonate humans on business help lines; very soon they will be able to convincingly impersonate you or me, with AI-generated deep fakes which look like us, speak like us, and know everything which we know.

In the very near future, when we’re online it will simply be impossible to know whether we are talking to a real human being, even someone we know well in real life. We may not care, though, because more and more we’ll be living in a completely immersive artificial reality individually curated to suit our own tastes.

A bigger problem is that it divorces us from direct experience and knowledge of the natural world just as climate change and species loss are making that experience and knowledge far more important. Becoming acclimatised to inhabiting a fully mediated reality, we risk being left with no interpersonal skills and no knowledge, and having lost the ability to memorise anything at all.

As a coach, and as an individual, I’m concerned with maximising human potential.

Wouldn’t it be a good thing to train our minds and memories so that we can recite poetry and stories off the cuff? Wouldn’t it be good if we once again had a whole industry dedicated to helping us do that?

We may never match the fictional skills of the Bene Gesserit – but body scan meditation really does develop awareness of subtle physical processes, not to mention its other benefits. This attention to neurological sensations helps to develop fine control of perceptions and muscular actions.

Combine that with developing physical fitness: fully inhabiting our real bodies, in the real world.

Isn’t that better than being isolated in a computer-generated world, where we never know who’s real and who’s not, and where our achievements are digital dreams?

Maybe we should all be thinking about training our minds and body to their fullest potential. It’s an old-fashioned concept which has never seemed more relevant.

And it’s never too late to start.

Photo by Ahmad Odeh on Unsplash