The Foreland Crags Where Giants Dwelled. Copyright 2026 the author. All rights reserved.

Route: Llangollen to World’s End and back. Wednesday 5th June, 2024

To the World’s End

Till that he neged full nigh in to the North Wales.

All the isles of Anglesey on left half he holds,

And fares over the fords by the forelonds,

Over at the Holyhead,

till he had eft bonk again

the shore In the wilderness of Wirral;

wonde there but lyte lived

That either God other gome with good heart loved

Today’s going to be a big day. I know that the terrain will be a lot steeper than most of my routes, so I’m a little apprehensive about that. On the other hand, I’m excited: I’m about to cross the fords by the forelands, and visit the Holy Head at World’s End.

A writer lives for sentences like that. It sounds like something from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but it’s a real place and I’m going there. My plans have changed; instead of visiting Dinas Brân and Valle Crucis Abbey today and walking to Wrexham tomorrow, I’ll walk to World’s End and back today, lightly laden, and catch the bus to Wrexham in the morning.

After a buffet cooked breakfast, and applying gel plasters to my blisters, I set off. It’s a short walk along the Dee.

The World in Song and Music

On my right, I see the site of the Llangollen International Eisteddfod. An eisteddfod was originally a bardic competition of music and poetry in the traditional strict metres. The first recorded eisteddfod that we know of was held in 1176, but it’s believed they were much older than that, perhaps dating back to the Roman or post-Roman era – and perhaps even earlier than that.

The National Eisteddfod of Wales was revived in the nineteenth century, and is the major annual event of Welsh-speaking society. During the Second World War, the event was visited by members of a number of European governments-in-exile, who were very impressed. Their reaction was the spark that led to the International Eisteddfod being created even while the war still raged, as an event where the peoples of the world could gather to celebrate the arts. It’s now grown to the point where thousands of people perform and tens of thousands attend to watch over the course of six days. The global cultural impact of this tiny nation, Wales, is impressive.

But that’s not my objective today: I’m in search of something very different: an important location on Gawain’s search for the Green Chapel and one of the few specific places named in the poem – though its location has long been forgotten until now. Soon I turn onto a side road leading to the Eglwyseg valley. My heart sinks: it looks almost vertical.

Over the Fords by the Forelands

Taken slowly, it’s not too bad: a pleasant little byway lined with hedges and foxgloves, and the nice thing about precipitous roads like this is that you don’t have to walk very far before you can turn and see a vastly expanded panorama.

Castell Dinas Brân on the horizon. Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

For a short while, Castell Dinas Brân is visible, but it soon gets hidden by the terrain; it’ll reappear from time to time, but I’m actually surprised at how little I see of it. Instead, as the climb begins to flatten, the skyline ahead is increasingly dominated by the rocks for which this valley is known: tall, blank cliffs of grey sandstone rising from the sharply-sloping valley sides, their bases hidden by a skirt of scree and rubble.

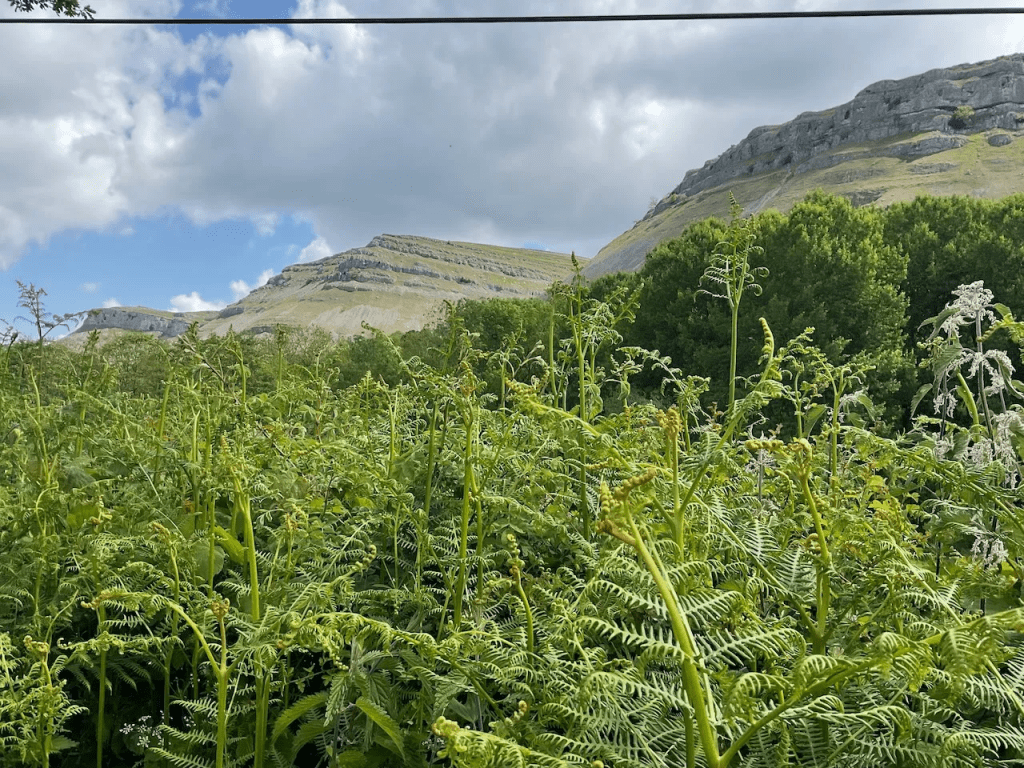

Towards the forelands. Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

Rain and streams run down these slopes, for most of history crossing the road in their quest to join the Afon Eglwyseg and tumble down to the Dee. There were many of these fords on the way to World’s End; the valley was known for them, until they were tamed and channelled through culverts early in the twentieth century. These surely must have been the fords of which the poet wrote, and I’m making my way through the forelands towards the Holy Head at the valley’s highest point.

Today, the valley is stunningly beautiful, peaceful and radiant in the sunshine. Small fields alternate with oak woodlands; sheep and ginger Highland cattle munch away or stare into the distance as I trudge past ancient farms and semi-derelict stone barns. The cold wind just makes the air fresher, and the energy of the land more vibrant. I feel like I did as a small child, when my parents took me on walks through the country lanes near our home. Until relatively recently, though, the valley looked very different; it was mostly filled with oak trees until the Second World War when many were felled to supply timber for the war effort.

The Stony Homes of Giants

These hills, low as they are relative to even elsewhere in Wales, can be bitter in winter. Even in the twentieth century, there are plenty of records of flocks of sheep being trapped in heavy snow, of cars being buried and their occupants stranded, and drinkers being trapped in the White Hart pub for days by a blizzard!

The right hand side of the valley, Eglwyseg Mountain, looms above me, its great grey cliffs reminiscent of Brutalist concrete architecture (Swansea unavoidably comes to mind). It’s not a random comparison; these hills were the homes of giants. It’s not clear whether they were thought to live underground or in primitive huts, but they weren’t friendly towards their human neighbours. Here had been the lair of the cannibal giantess slain by Saint Collen. As she fought Collen, this giantess called to another giant, a male, who lived in Craig Arthur, close to World’s End, but he didn’t come to her aid.

All of this makes the Egwlyseg valley completely consistent with of Gawain’s journey – in a desolate midwinter, he would be struggling through a bleak, leafless, oak forest, following a muddy trail flooded by fords, while man-eating giants called to each other from their watchpoints atop the high cliffs all around…

A Colonel and a King’s Head

As he made his way up towards the valley head, Gawain would have come to a dwelling: one which was there in the 14th century, and which would certainly have been known to Glyndŵr and the Pearl Poet. This is Plas Uchaf. Here, there’s an odd connection to Gawain and the Green Knight; one that the Poet couldn’t have known about, because the events concerned occurred centuries after his death. It’s a connection with decapitation – because Plas Uchaf was home to Colonel John Jones Maesygarnedd, so called after his home in Meirionydd – and Jones was a regicide, one of the men who signed the death warrant of King Charles I.

Today, I peer at the small stone-built house through iron gates.On the other side,, a Highland cow regards me with no great interest from its pen. Jones’s home is now the office for an organic farm, whose signs I’ve noticed on gates as I passed. Plentiful as well have been signs warning of cameras and security protection; the valley may be remote, but it seems it’s still vulnerable to dangers and wild men.

Maesygarnedd itself is also a small stone farmhouse set at the very head of a remote upland valley. That’s where Jones grew up, moving to Plas Uchaf later in his eventful life. His ownership of both allowed him to stand for both Merionethshire and Denbighshire in the parliamentary elections of 1656, the first to be held after Cromwell’s victory. He opted to take up the Merionethshire seat, though a portrait of Cromwell – Jones’s brother-in-law – reputedly hung in Plas Uchaf for centuries after. Following the restoration of the monarchy, Jones was arrested by Charles II’s men, tried, and sentenced to the terrible traitor’s death that’s been the fate of so many Welsh leaders across the centuries at the command of English kings: to be hung, drawn, and quartered. Witnesses reported that he met his end with courage and dignity.

The Head of the Valley

Turning my back to the regicide’s home, I begin the last ascent towards World’s End. Here, approaching its head, the valley is heavily wooded; as idyllic in its way as the pastures further down. Oak and pine sway lightly in the breeze, their green cover enlivened by the occasional copper birch and splashes of pink from the rhododendron undercover. As I advance – the same old story, take a few steps, rest a few moments, just keep going – the sunlight is softened by its passage through the canopy. The scent of earth and leaves is invigorating; every breath a draught of life-energy. I pass a few sheep in a small pen by the roadside. I feel not just alive but supercharged; the nwyfre (what the Chinese call qi) is strong here. Everything feels super-real: this is one of the thin places, where Annwn, the Otherworld, is very near. When Gawain came through, though, in the depth of winter, it wouldn’t have felt anything like as comforting. A bitter and harsh passage, it would have been for him.

The Final Ford

Despite the incline, it isn’t long now before I reach the sharp bend at the very top of the valley, where the road switches from the right slope to the left on its last climb up to the plateau. Here, right in the bend, is the last and largest of the fords. It’s shallow enough to walk through – but deep enough to come up over my boots if I did. Fortunately, there are stepping stones right on the edge of the road, just above a steep drop. At least one of which rocks, just enough to startle the unwary and make the heart miss a beat…

Approaching the final ford. Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

It’s here that I find what I’ve come to see: the great crag that looms over the ford, looking down over the forelands through which I’ve approached.

The poem tells us that Gawain “fares over the fords by the forelands; from the Holy Head, before reaching the banks of the wilderness of Wirral”.

To the Holy Head – and Over

What did the poet mean by “the Holy Head”? Modern editors of the poem – Tolkien, Gordon and Davis – agreed that the landmarks in the poem must have referred to places that his audience would have known, but no modern scholar has been able to identify them, or say where the fords were. Having now crossed those fords, I’m convinced that I’m now at the Holy Head: a place that Glyndŵr and his Marcher peers would have recognised from the poet’s words.

This wall of stone is ‘Craig y Forwyn’: the Rock of the Virgin. Nobody today is sure where the name comes from, and most sources simply repeat the tale that a young woman, rejected in love, threw herself from the top of the cliff in despair. This originated with George Borrow, who came this way before getting himself lost in the moss and heather on top of Ruabon Mountain. Asking a local man, this is the suggestion he received, though the man himself wasn’t sure. It’s not a particularly reliable explanation, let’s say.

So where might the name come from, and why might the Pearl Poet and Glyndŵr have understood the reference to ‘the Holy Head’ as meaning this remote valley head? As so often with this project, I’ve found a key clue in an obscure book by a local historian.

Follow this road upwards and it becomes a single-lane track, winding its way across the moorland top of Ruabon Mountain. If it hadn’t been for my blisters, this is the route I would have followed until I reached the village of Minera. From there, I would have followed the A525 into Wrexham, where I’m booked into the Wynnstay.

I turn back – but the road continues. Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

Gawain, though, would have continued from Minera along what is now the B5102 through what was then empty land and forested hunting grounds towards Cefn-y-Bedd – the grave of Gwrle Gawr, yet another giant. This was inhabited by independent Welsh tribes known as the ‘progenies of Ken’ He could head towards Hawarden and the ancient fortress whose ownership triggered Edward I’s conquest of Wales. Very quickly, Gawain would be in the Wirral. It fits perfectly with the poem’s itinerary.

The Virgin in the Rock

All around that track above World’s End, though, lies empty moor. During the Blitz, the authorities lit fires there at night. Shining brightly in the darkness, they fooled the pilots and navigators of German bombers, who mistook them for the Liverpool docks – and dropped their bombs there instead of over their real target. It was a great success – but there was an important, though unmourned, casualty. Local historian David Crane records that from the cliff-face of Craig y Forwyn there once rose a pillar of rock resembling a robed woman – until she was blown apart by one of those Luftwaffe bombs.

A robed woman in the rock at the very head of the valley leading down to Castell Dinas Brân and the Abbey of Valle Crucis: the Valley of the Cross. That’s Eliseg’s cross, which had proclaimed the Christian faith of the Welsh for five centuries by the time Glyndŵr was born. This was the valley where the soldier-saint Collen slew giants – nothing new for Gawain, who had giants of his own to fight. They pursued him from high rocks, says the poem: surely the high rocks of Eglwysleg? Who would the poet and his audience have identified as the woman in the robe, standing clear from the precipice? Surely the Virgin: Mary, mother of Christ. Mary, whose image was painted inside Gawain’s shield, as it had been on Arthur’s at Badon Hill.

Craig y Forwyn has a neighbour: Craig y Cythraul, the Rock of the Devil. Truly, it’s the world’s end.

Looking back to Llangollen from World’s End. Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

The Mystery Solved

If the Gawain poet knew Welsh – and by this point in our journey we know that he must have – then he knew that ‘Pen’ translates into English as ‘head’ but also as ‘highest point’. When he wrote of the ‘Holy Head’, this is where he meant: a pillar shaped like the Virgin, at the head of this enchanted valley high above Llangollen.

I eat my sandwiches and retrace my steps, back to the Hand Hotel by the Dee.

Leave a comment