The Tower on the Brow. Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

Route: Chester to Wallasey and back by train. Tuesday 20 August, 2025

Into the Wirral Wilderness

Gawain finally makes it to the wilderness of the Wirral: a short peninsula jutting out into the Irish Sea, with the estuary of the Dee to one side, that of the Mersey to the other, and Liverpool across the water.

This, we’re told, is a place where no-one dwells who loves either God or other men. That reflects the reality of the fourteenth century, when it was a neglected royal hunting ground. Reserved for the sovereign, it was beyond the authority of civil law. Order was supposed to be maintained by a Crown appointee, the Forester… but the noblemen who held this office had rarely made the effort. The King, after all, was very far away.

A Lawless Land

This wasn’t just geographical distance. The Wirral was a part of the Earldom of Chester, and the Earls were Earls Palatine – meaning that they were essentially sovereign, since the Kings of England, recognising Chester’s strategic location close to the Welsh borders, had long since delegated their royal authority to the Earls. Until 1237, these had been Norman Marcher lords, but by the time of Glyndŵr and the Pearl Poet it had become a title awarded to the heir to the throne, along with the role of Prince of Wales.

When Owain Glyndŵr was growing up, this was Edward, the Black Prince, who spent his time campaigning abroad before dying of dysentery in 1376. The titles descended in turn to his son Richard, who became King the next year, when his grandfather Edward III died after fifty years on the throne. Richard, now Richard II, was only ten years old. He never married or had children, and was deposed in 1399 by Henry Bolingbroke, who became Henry IV.

All of this meant that there was a power vacuum in Cheshire, and that vacuum bred chaos. Chester itself became utterly lawless, a stronghold of thieves, murderers and cattle raiders. The same held true of the Forest of Wirral, which had become the lair of outlaws and other outcasts from society. They were such a menace that even the rogues of Chester complained, persuading the Black Prince to cancel the peninsula’s status as royal land in the same year that he died. This made little difference to the outlaws.

And into this rides Gawain, alone on his horse: tired now from days of journeying, and still with no idea where he might find the Green Chapel and fulfil his bargain with the Green Knight.

The Fort of the Legions

I arrive in rather more comfortable circumstances. From Llangollen I’d gone on to Wrexham, stayed the night, then moved to Chester for a few days. I’m staying in a Travelodge just across the road from the remnants of the amphitheatre where the Romans of this fortress city once watched gladiators’ strife. It’s also a couple of minutes’ walk from an ancient sandstone church. In fact, it’s the Church of Saint John the Baptist, where in September 1386 Owain Glyndŵr and others gave their testimony in the lawsuit of chivalric honour, Scrope versus Grosvenor. To my enduring chagrin, I don’t actually realise this until after I’ve left town.

I get the train from Chester’s bustling station, change at Birkenhead and go… where?

The Island of the Welsh

While I was dreaming up this project I was engaged in postgraduate studies in the field of Applied Linguistics, and as a result had access to an online university library. I’ve read as many academic papers on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as I can find and there are a couple of old manors, Storeton and Hooton, which are speculatively associated with possible authors. Neither really gives me the right vibe, though. Once again, I allow my intuition to do the thinking… and it directs me to Wallasey.

I leave the train at Wallasey Village. I reason that if Gawain had come to the Wirral he would have come here, right to the furthest end. Here, a hill rises from what was once a great bog. Wallasey means ‘ the island of the Welsh’, and the dank waters of the marshes would have made it an island indeed.

How did it get its name?

The Black-Draped Chair

It’s not so long ago that the Wirral was very Welsh, despite being in England. Liverpool’s industrial expansion during the Industrial Revolution drew huge numbers of Welsh across the border: so many of them that in 1917 the National Eisteddfod of Wales was held here. This was the tragic Eisteddfod of the Black Chair: the winning poet, Ellis Humphrey Evans, whose poem had been submitted under his bardic nom-de-plume Hedd Wyn (Blessed Peace), had been killed in action during the Battle of Passchendaele only days before. His prize, the Eisteddfod chair awarded to the year’s chief bard, was draped with a black cloth before being transported to his family home in Trawsfynydd, Gwynedd. Another Welsh-speaking Welshman from Wirral, a young lieutenant, had been seriously wounded in battle a couple of months earlier. This was Saunders Lewis, who had been born and grown up here in Wallasey, and who would go on to form the Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru, the Welsh National Party which, as I write, appears to be on the verge of finally forming a Welsh government.

But that’s all from recent times. Back in the day when the poet was writing the tale of Gawain’s quest, the Wirral was largely empty, with few legitimate inhabitants. Who were the Welsh who gave Wallasey its name?

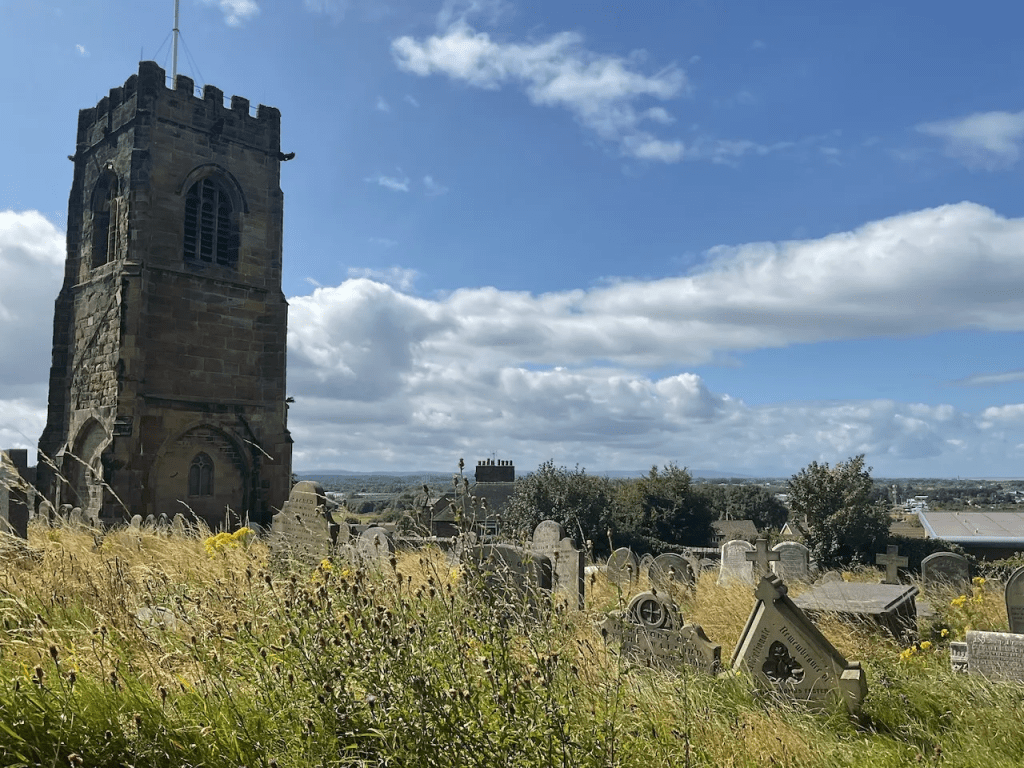

A Hilltop Tower

Arriving at Wallasey Village railway station, I find myself acutely aware that I haven’t had any breakfast. I fortify myself with an excellent bacon sandwich and a spiced chai latté at Stollie’s Café before heading to the hill’s summit, known locally as the Brow, where a church stands. This is St. Hilary’s: one of very few in Britain dedicated to this saint. This caught my eye when I was planning my trip, since one of the others lies just outside my home town of Cowbridge in the Vale of Glamorgan: I sense the tug of synchronicity.

There’s been a church here on the Brow since at least the eleventh century, when the first known stone church was constructed by a Norman lord. However, dedications to St. Hilary are usually associated with St. Germanus, who visited Britain from Gaul in the fifth century to campaign against the heretical Christianity of Pelagius, so it would seem that by the time the Normans arrived there may already have been a church of some kind here for around six hundred years.

The current church was built in 1859, replacing a Tudor church destroyed by a fire in1857. The tower of that older church remains, standing alone in the churchyard and oddly reminiscent of St. Michael’s Tower on Glastonbury Tor.

Gawain would have made for this high point to survey the land – and his options. He’s searched through the wild lands of Wales with no success. From here, he looks back towards the Cheshire plain, knowing that his goal is not to be found in those settled lands. Where ought he go next?

The Realm of Logres and the Old North

To the poets of Wales and the Marches, the Mersey marked the northern boundary of Logres, the area of southern Britain that had been governed by civil authority under the Romans: Britannia Prima. North of the Mersey and Humber was Northumberland, the Romans’ military zone of Britannia Secunda. The memory of the empire endured – and so did the sense that north of the Mersey lay a different land, with different rules. The Green Knight and his Chapel were not to be found there, so Gawain would not have gone north into the Lake District and the ‘Old North’ of the Welsh.

He would have looked to the East. From here, on the Brow, he would have seen, as I can see, the dark mass of the Peak District. He would have known, now, that there was nowhere else left where his destination might lie.

The Welsh Arthur and a Wise Old Bird

Owain Glyndŵr and his peers, probably including the Pearl Poet, would have known the Wirral as Cilgwri, and as the mythical home of the ancient ousel, or blackbird which was consulted by King Arthur’s men in their search for Mabon mab Modron – a tale which was, as the Pearl Poet was writing Sir Gawain, being written down in the Red Book of Hergest at the command of Hopcyn ap Tomos ab Einion Offeiriad… It makes sense that she would have dwelt on the uppermost point of the Wirral: the Brow of Wallasey.

A Magical War of Poets Over Powys

An idea has been growing in my mind for a while now… the idea of a war of poems and magic raging through Wales and the March… A war of words and visions, laying out the line of a wider Wales; a Wales that it seemed might be conjured back into existence through persuasion… and force of arms…

Here, on the Brow, came Arthur’s knights in search of Mabon. From here, they can see the line of the Mersey and the hills of Staffordshire… They go on to Gloucester and the Severn.. In the Third Branch of the Mabinogi, Manawydan and Pryderi dwell in Hereford, Worcester, Gloucester and Chester.

From Wallasey to Chester and east to the Peaks, then south to Worcester and Gloucester and Hereford… It’s a route that looks very much like the old borders of ancient Powys. We’re going to see in our next chapter that this line was very much on Glyndŵr’s mind – and that he tried to make those lands Welsh once more. Had the tales of the Mabinogion and of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight been preparing the ground for this, sowing the seeds of the idea of the Welsh returning to their ancestral lands?

Brow to Beach

From the Brow, I walk downhill to Wallasey Beach. From the red brick streets I emerge into a scrubland, heading for a chain-link fence signposting a Harvester restaurant. The road passes over sand dunes to a low rise where a church of St. Nicholas sits in the foreground. In the southeast distance, I can see the more southerly stretches of the Peak District.

The Work of Giants? Copyright the author, 2026. All rights reserved.

Below me, the Art Deco building which now houses the Harvester sits next to the beach, fully exposed to the sea wind which clutches and tugs at my clothes. In the car park, an ice-cream van patiently waits for a visit from one of the walkers throwing balls on the beach for their delighted dogs. To the south-west rises the dark massif of Snowdonia: I can clearly see the three-peaked summit of Yr Eifl, topped by the prehistoric settlement of Tre’r Ceiri, the Town of the Giants. To the west, enormous wind turbines rise in straight lines from the choppy waters of the Irish Sea. I’ve never actually seen turbines in the sea before; their sheer size so close to the shore inspires a sense of awe and wonder, but they seem out of place: a sign of man’s hubris in a place where we should be contemplating the raw beauty of nature. Far in the future, people will say they must surely be the work of giants.

The Birth of England and the Last Stand of the Men of the North

This beach may be another reason why Wallasey gained its name. A few miles away lies the village of Bromborough, which has been suggested as potentially the location of the Battle of Brunanburh in 957. On one side of this blood-soaked encounter was the army of Aethelstan, who had begun as King of Mercia before inheriting the crown of Wessex as well. He had gone on to defeat the Vikings who ruled the north of England from York, and so became the first Anglo-Saxon king to rule the whole of England.

However, this wasn’t England as we know it today: much of modern Cumbria was ruled from Govan (near Glasgow) as part of the British kingdom of Strathclyde. This was a Brythonic culture, speaking a language very similar to Welsh, which was ruled by Owain ap Dyfnwal. Owain’s forces were part of a three-kingdom coalition opposing Aethelstan’s expansionist policies; the others were the kingdom of Scotland, ruled by Constantine II, and the Norse-Gael kingdom of Dublin under Olaf Guthfrithson.

The opposing armies met at Brunanburh; the battle was a resounding victory for Aethelstan. The Norse-Celtic forces were routed amongst scenes of great slaughter. The Danish army had come by ship, and it’s quite possible that the Scots had done the same. The long strand of Wallasey Beach might have seemed a secure spot to beach their craft before marching inland, and perhaps it was from here that the survivors managed to escape – and we know from the chronicles that there were survivors from both of these armies.

History is silent, however, on the fate of the Britons, the Welsh, of Strathclyde. I wonder, did they provide a rearguard on Wallasey Brow, holding back the Saxons while their allies escaped? Or did they make a final muster here, gazing out to sea in vain hope of rescue while their numbers dwindled? Perhaps ‘Wallasey’, ‘the Island of the Britons’, commemorates the hill where Owain’s men made their last stand…

All we can say now is that the Poet must have had good reason for sending Gawain into the Wirral. Perhaps it was indeed to remind the Welsh of his day about the Ousel, and of the days when their ancestors ruled the land where that wise old bird was to be found.

As for me, I head back to Chester. Tomorrow, knowing now that they form no part of Gawain’s tale, I’ll be heading on a side-quest to the holy wells of Gwenffrewi and her uncle Beuno at Holywell. Tonight, I’ll enjoy good beer at the Bear and Bull, an ancient pub right next to the Dee, at the point where the river ceases to be tidal – and the reason why Roman and medieval Chester was a sea port.